Discover posts

Greetings Family!

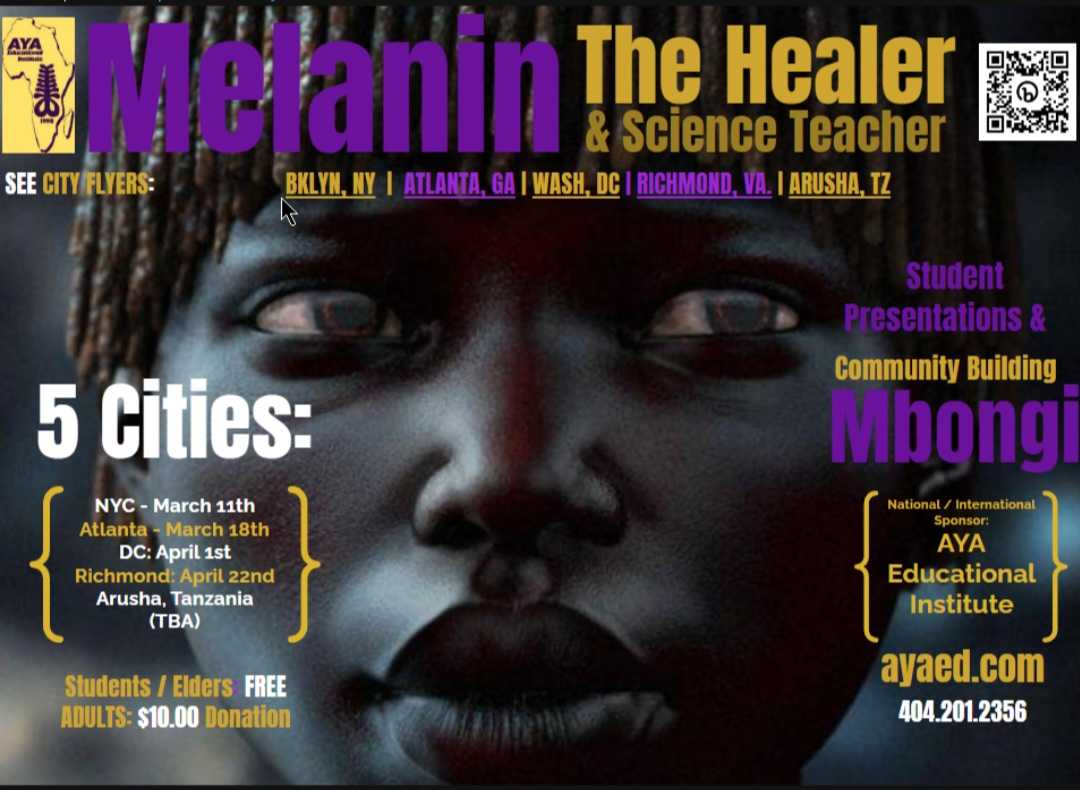

I am asking my family to come out and support my teen daughters who will be participating in their Afrikan centered homeschool Mbongi -Melanin Healing science event. They will be presenting their BioKemistry projects on stage in front of our community on April 29, 2023 at 11am in Brooklyn, New York. Site location will be provided soon. There are 3 other events, this weekend in DC, brother Tony Browder is a special guest, Richmond VA, Tanzania Africa and we saved the best for last....BROOKLYN!!!!

If you can't appear then I will post up the Zoom link soon so you can watch it virtually. You can also support monetarily. This school is run by Baba Wekesa Madzimoyo and Mama Afiya Madzimoyo. They have been teaching for 25+ years. Please text or message me for more information. We must step out and support our youth. Peace to the Gods & Goddesses.